Global Market Outlook 2020: Exclusive Market Insights & Forecasts

How the “Known Unknowns” are Likely to Affect Currencies

The year that just ended has been one of political turmoil, global uncertainty caused by Trump’s trade war, economic slowdown, and yet record-high stock prices coupled with near hibernation in the FX market. The year just starting is shaping up to be even more dramatic politically, with Brexit from January and the US impeachment trial and Presidential election later in the year. How will this affect currencies? Which currencies might benefit, and which might suffer?

First let’s look at why all this Sturm und Drang failed to make much of an impression in 2019.

There’s no doubt that the FX markets were in the doldrums in 2019. If we look at the range between the high and the low of each currency pair over a six-month window, we can see that the average hit the lowest level in two decades in July and ended the year not far off.

The narrow range is also evident if we look at how the various currencies performed during the year vs the USD. The difference between the best-performing currency (CAD) and the worst-performing (SEK) was 10.4%, the second-narrowest range in the last decade. In fact, it’s the third-narrowest in the last 30 years (2004 was 5.8%).

The narrow range is also evident if we look at how the various currencies performed during the year vs the USD. The difference between the best-performing currency (CAD) and the worst-performing (SEK) was 10.4%, the second-narrowest range in the last decade. In fact, it’s the third-narrowest in the last 30 years (2004 was 5.8%).

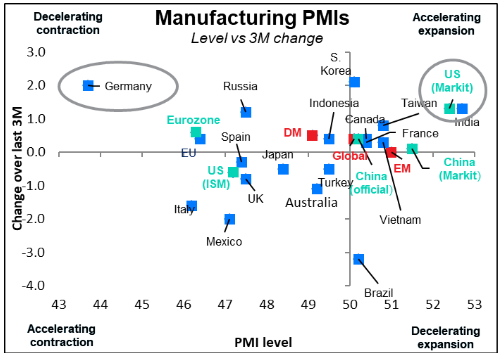

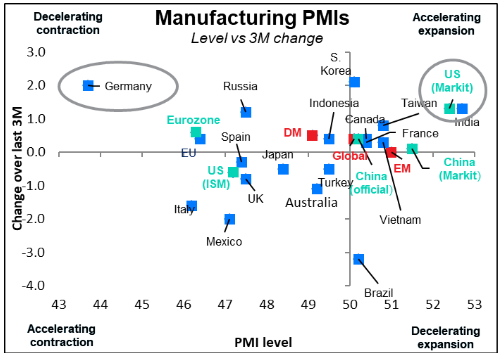

The main reason for this narrow range, I believe, is the narrowing dispersion in economic performance among countries. If we look at the manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major currencies, the dispersion among them came down as the PMIs themselves came down. (Dispersion rose from June to September but fell after that.)

The main reason for this narrow range, I believe, is the narrowing dispersion in economic performance among countries. If we look at the manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major currencies, the dispersion among them came down as the PMIs themselves came down. (Dispersion rose from June to September but fell after that.)

Similarly, monetary policy also converged among the major countries. Policy rates came down for most major countries during the year. As they approached or pierced the zero bound, they tended to converge, since there is a limit to how low they can go.

Similarly, monetary policy also converged among the major countries. Policy rates came down for most major countries during the year. As they approached or pierced the zero bound, they tended to converge, since there is a limit to how low they can go.

Outlook for 2020: monetary convergence but economic divergence

This year, I expect we’ll see continued monetary policy convergence but increased economic divergence.

The market doesn’t see monetary policy pulling us out of these ranges in 2020. Most central banks are expected to be on hold during the coming year, with less than a 50-50 chance of a rate cut for most countries (and virtually no chance of a hike). Only Britain and Australia are seen as likely to cut. In the US, the market still expects a cut sometime in the second half, but the people making the decision – the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) themselves -- don’t.

In fairness, I should say that these rate forecasts are by no means guaranteed. For example, at the end of last year the market saw only a 13% chance of even one rate cut during 2019 in the US, but in the event there was not one but three cuts.

Outlook for 2020: monetary convergence but economic divergence

This year, I expect we’ll see continued monetary policy convergence but increased economic divergence.

The market doesn’t see monetary policy pulling us out of these ranges in 2020. Most central banks are expected to be on hold during the coming year, with less than a 50-50 chance of a rate cut for most countries (and virtually no chance of a hike). Only Britain and Australia are seen as likely to cut. In the US, the market still expects a cut sometime in the second half, but the people making the decision – the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) themselves -- don’t.

In fairness, I should say that these rate forecasts are by no means guaranteed. For example, at the end of last year the market saw only a 13% chance of even one rate cut during 2019 in the US, but in the event there was not one but three cuts.

However, economic performance may start to diverge as one of the major issues the currency market faced in 2019 will be less an issue in 2020: trade.

Trade has been the major uncertainty in the US since Trump started the trade war with China.

However, economic performance may start to diverge as one of the major issues the currency market faced in 2019 will be less an issue in 2020: trade.

Trade has been the major uncertainty in the US since Trump started the trade war with China.

All other major policy categories are currently at or below-average uncertainty, especially the two that the FX market usually focuses on: fiscal and monetary policy.

All other major policy categories are currently at or below-average uncertainty, especially the two that the FX market usually focuses on: fiscal and monetary policy.

It looks like trade will be much less of an issue in 2020 than it was in 2019. The US and China have signed “Phase One” of their trade agreement. While much of the details remain unclear, what is clear is that the US wants the issue resolved ahead of the November election so Trump can present some “wins” to those voters who still support him – not to mention get soybean prices up. At the same time, the US, Mexico and Canada finally signed the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The #1 problem that faced global financial markets in 2019 should be much less of a problem in 2020. That would be an enormous change. (Although of course we must remember those old sayings, “There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip” and “don’t count your exports until they’ve shipped.”)

The tit-for-tat tariffs had a huge impact on global trade and business sentiment. Many central banks also specifically mentioned trade uncertainties when explaining why they were cutting interest rates or keeping rates low.

It looks like trade will be much less of an issue in 2020 than it was in 2019. The US and China have signed “Phase One” of their trade agreement. While much of the details remain unclear, what is clear is that the US wants the issue resolved ahead of the November election so Trump can present some “wins” to those voters who still support him – not to mention get soybean prices up. At the same time, the US, Mexico and Canada finally signed the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The #1 problem that faced global financial markets in 2019 should be much less of a problem in 2020. That would be an enormous change. (Although of course we must remember those old sayings, “There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip” and “don’t count your exports until they’ve shipped.”)

The tit-for-tat tariffs had a huge impact on global trade and business sentiment. Many central banks also specifically mentioned trade uncertainties when explaining why they were cutting interest rates or keeping rates low.

What might be the implications of fewer trade worries?

Less “risk-on, risk-off” movement. Many trading sessions were dominated by whatever ambiguous tweet or headline in China’s Global Times appeared that day. Fewer such interjections may result in less volatility for the AUD/JPY. In theory it should also result in a higher AUD/JPY too, but of course that depends on there being no other risks to take its place – something I wouldn’t be so sure of. Just look at what happened with the US and Iran recently.

Less likelihood of rate cuts Many central banks have pointed to trade concerns as weighing on their economies. For example, ECB President Lagarde said last month that “The ongoing weakness of international trade in an environment of persistent global uncertainties continues to weigh on the euro area manufacturing sector and is dampening investment growth.” Similarly, the Bank of Canada said, “ongoing trade conflicts and related uncertainty are still weighing on global economic activity, and remain the biggest source of risk to the outlook.” If the global trade disputes die down, that could relieve some of the concerns of central banks. It doesn’t make rate hikes more likely, but it could make rate cuts less likely. That would mean less monetary policy convergence at the bottom and greater support for those currencies with relatively higher interest rates: USD, CAD, and NZD.

What might be the implications of fewer trade worries?

Less “risk-on, risk-off” movement. Many trading sessions were dominated by whatever ambiguous tweet or headline in China’s Global Times appeared that day. Fewer such interjections may result in less volatility for the AUD/JPY. In theory it should also result in a higher AUD/JPY too, but of course that depends on there being no other risks to take its place – something I wouldn’t be so sure of. Just look at what happened with the US and Iran recently.

Less likelihood of rate cuts Many central banks have pointed to trade concerns as weighing on their economies. For example, ECB President Lagarde said last month that “The ongoing weakness of international trade in an environment of persistent global uncertainties continues to weigh on the euro area manufacturing sector and is dampening investment growth.” Similarly, the Bank of Canada said, “ongoing trade conflicts and related uncertainty are still weighing on global economic activity, and remain the biggest source of risk to the outlook.” If the global trade disputes die down, that could relieve some of the concerns of central banks. It doesn’t make rate hikes more likely, but it could make rate cuts less likely. That would mean less monetary policy convergence at the bottom and greater support for those currencies with relatively higher interest rates: USD, CAD, and NZD.

Better performance for Europe

Germany is the dominant economy in Europe, with twice the impact on overall Eurozone GDP that would be expected simply from its weighting in EU statistics. And Germany has been the major victim of the global trading slowdown, not China. An improved trade picture suggests a better German economy and therefore perhaps a higher EUR/USD.

Better performance for Europe

Germany is the dominant economy in Europe, with twice the impact on overall Eurozone GDP that would be expected simply from its weighting in EU statistics. And Germany has been the major victim of the global trading slowdown, not China. An improved trade picture suggests a better German economy and therefore perhaps a higher EUR/USD.

Better performance for China, too

It’s only reasonable that the Chinese economy would benefit from the end of the trade war too. However, it’s hard to say if China’s current economic problems stem from international trade or from domestic debt woes. If indeed China’s economy did pick up, that would be positive for the commodity currencies, especially the AUD.

A weaker dollar

The dollar tends to benefit during extreme periods either way. When times are good, usually the US economy is among the best-performing economies, US interest rates move up, and the dollar does well. When times are bad, global investors look for a safe-haven, and the dollar is the safest haven of all.

But when times are so-so – not great but not bad either – the dollar tends to perform mediocrely. That could be the case this year too.

One possible exception: as shown above, dollar interest rates are the highest among the G10 countries. In a more stable environment, the USD could find demand as an asset currency for G10 carry trades. I think this is somewhat of a low possibility however, as carry trades are no longer as big a factor in the FX market as they used to be.

Better performance for China, too

It’s only reasonable that the Chinese economy would benefit from the end of the trade war too. However, it’s hard to say if China’s current economic problems stem from international trade or from domestic debt woes. If indeed China’s economy did pick up, that would be positive for the commodity currencies, especially the AUD.

A weaker dollar

The dollar tends to benefit during extreme periods either way. When times are good, usually the US economy is among the best-performing economies, US interest rates move up, and the dollar does well. When times are bad, global investors look for a safe-haven, and the dollar is the safest haven of all.

But when times are so-so – not great but not bad either – the dollar tends to perform mediocrely. That could be the case this year too.

One possible exception: as shown above, dollar interest rates are the highest among the G10 countries. In a more stable environment, the USD could find demand as an asset currency for G10 carry trades. I think this is somewhat of a low possibility however, as carry trades are no longer as big a factor in the FX market as they used to be.

Lower precious metals

Gold and silver have been beneficiaries of the increase in global risk during the year. With this risk gone, they may retrace some of their gains, assuming of course that nothing takes the place of trade as a new global risk – hardly a sure bet (again, Iran is “Exhibit A” here). There are always the “unknown unknowns” that we have to worry about. Also, a weaker dollar would temper the decline as gold tends to appreciate in dollar terms when the dollar weakens.

Lower precious metals

Gold and silver have been beneficiaries of the increase in global risk during the year. With this risk gone, they may retrace some of their gains, assuming of course that nothing takes the place of trade as a new global risk – hardly a sure bet (again, Iran is “Exhibit A” here). There are always the “unknown unknowns” that we have to worry about. Also, a weaker dollar would temper the decline as gold tends to appreciate in dollar terms when the dollar weakens.

Brexit: still a risk

With the Conservatives winning a decisive victory on the promise to “Get Brexit done,” will we finally be finished with this long-running drama on 31 January? Hah! True, the UK will probably leave the EU on schedule on 31 January. However, that won’t be the end of Brexit – it will just be the end of the beginning. In fact, the real battle will begin as soon as Britain leaves. Once Britain withdraws from the EU, the clock starts ticking for Britain and the EU to establish the nature of their new relationship. That’s actually a much harder task than the terms of the withdrawal. Furthermore, Britain will have to negotiate trade relationships with most other countries in the world at the same time.

And then there’s the question of “Scexit” and “Nixit” – Scotland and Northern Ireland leaving the UK. The former at least seems to be analogous to Catalonia as an issue even though the central governments oppose it.

GBP turned around from its lows and finished the year as the second-best-performing major currency in 2019 (best performing if you measure from the first trading day of 2019 to the last). Markets were reassured that a) Britain wouldn’t crash out of the EU without an agreement, and b) the appalling Jeremy Corbyn wouldn’t become PM. I’d be astonished though if that good performance were to be repeated in 2020. Given how long it’s taken Britain just to agree on a Withdrawal Agreement, I can’t see how they can work out a new trade agreement by the end of the year even if PM Johnson has written it into law. As a result, more uncertainty is in store for the GBP in 2020. Under those conditions, the Bank of England will have to keep rates unchanged at best – and the recent sluggish economic performance makes it likely that they’ll have to cut at least once during the year. I think GBP, the second-best performing currency of 2019, could be the worst of 2020.

Brexit: still a risk

With the Conservatives winning a decisive victory on the promise to “Get Brexit done,” will we finally be finished with this long-running drama on 31 January? Hah! True, the UK will probably leave the EU on schedule on 31 January. However, that won’t be the end of Brexit – it will just be the end of the beginning. In fact, the real battle will begin as soon as Britain leaves. Once Britain withdraws from the EU, the clock starts ticking for Britain and the EU to establish the nature of their new relationship. That’s actually a much harder task than the terms of the withdrawal. Furthermore, Britain will have to negotiate trade relationships with most other countries in the world at the same time.

And then there’s the question of “Scexit” and “Nixit” – Scotland and Northern Ireland leaving the UK. The former at least seems to be analogous to Catalonia as an issue even though the central governments oppose it.

GBP turned around from its lows and finished the year as the second-best-performing major currency in 2019 (best performing if you measure from the first trading day of 2019 to the last). Markets were reassured that a) Britain wouldn’t crash out of the EU without an agreement, and b) the appalling Jeremy Corbyn wouldn’t become PM. I’d be astonished though if that good performance were to be repeated in 2020. Given how long it’s taken Britain just to agree on a Withdrawal Agreement, I can’t see how they can work out a new trade agreement by the end of the year even if PM Johnson has written it into law. As a result, more uncertainty is in store for the GBP in 2020. Under those conditions, the Bank of England will have to keep rates unchanged at best – and the recent sluggish economic performance makes it likely that they’ll have to cut at least once during the year. I think GBP, the second-best performing currency of 2019, could be the worst of 2020.

US impeachment & election

There’s going to be an impeachment trial in the US Senate soon. Given the Republicans’ stated refusal to obey their sworn oath and act as an impartial jury, it’s likely that the impeachment won’t result in Trump’s conviction – although you never know, anything could happen: the Republicans could have a change of heart; he could resign rather than face the trial; he could have a heart attack; or he could even flee to Russia! (Russian TV has already referred to Trump as their ‘agent’ and asked if they should get an apartment ready for him.)

The impact on the dollar is therefore likely to be similar to the impact of the ridiculous Clinton impeachment trial, i.e. not much impact at all. In fact the dollar rose once the Senate trial began in that instance.

US impeachment & election

There’s going to be an impeachment trial in the US Senate soon. Given the Republicans’ stated refusal to obey their sworn oath and act as an impartial jury, it’s likely that the impeachment won’t result in Trump’s conviction – although you never know, anything could happen: the Republicans could have a change of heart; he could resign rather than face the trial; he could have a heart attack; or he could even flee to Russia! (Russian TV has already referred to Trump as their ‘agent’ and asked if they should get an apartment ready for him.)

The impact on the dollar is therefore likely to be similar to the impact of the ridiculous Clinton impeachment trial, i.e. not much impact at all. In fact the dollar rose once the Senate trial began in that instance.

The US election should also be no obstacle to the dollar. On average, the dollar has risen during election years since 1976:

The US election should also be no obstacle to the dollar. On average, the dollar has risen during election years since 1976:

If we look at the range, from the worst-performing election year to the best, we see that even in the year with the worst performance, the dollar was fairly stable after the election.

If we look at the range, from the worst-performing election year to the best, we see that even in the year with the worst performance, the dollar was fairly stable after the election.

There is some question about what will happen to the dollar if and when Trump loses and a Democrat wins, particularly if the Democrat candidate is someone who isn’t particularly popular with Wall Street, such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. The fact is that historically, the dollar has done better under Democrats than Republicans, but initially that might not be the case if the new President is thought to be a radical break to past policy.

There’s an even more interesting issue brewing with regards to the Presidency. News has been seeping out about Vice President Pence’s involvement in the Ukraine scandal. If Pence is also impeached and convicted along Trump, then US House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi would automatically become President. It’s a low probability event but not beyond the realm of possibility.

Finally, the regional Fed presidents who vote on the FOMC rotate every year. This year, two extremely hawkish people – Boston’s Eric Rosengren and Kansas City’s Esther George – will be replaced by two somewhat less hawkish people – Cleveland’s Loretta Mester and Philadelphia’s Patrick Harker. Pretty dovish Charles Evans from Chicago will be replaced by centrist Robert Kaplan of Dallas, while uber-dove James Bullard, of St. Louis, will be replaced by uber-uber dove Neel Kashkari.

Furthermore, Trump has nominated the very dovish Christopher Walker, the director of research at the St. Louis Fed, and the bizarre gold standard advocate, Judy Shelton, for the Fed’s Board of Governors. Walker is a conventional candidate and should have no problems being approved. Shelton is a bit more problematic. In any case, Walker should also help to tilt the discussion.

Net net, the composition of the FMOC will be slightly more dovish or less hawkish, whichever way you want to look at it. No one was forecasting a hike in rates anyway, but this change makes it more likely that US rates can only go down, not up, in 2020. That should be negative for the dollar at the margin.

There is some question about what will happen to the dollar if and when Trump loses and a Democrat wins, particularly if the Democrat candidate is someone who isn’t particularly popular with Wall Street, such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. The fact is that historically, the dollar has done better under Democrats than Republicans, but initially that might not be the case if the new President is thought to be a radical break to past policy.

There’s an even more interesting issue brewing with regards to the Presidency. News has been seeping out about Vice President Pence’s involvement in the Ukraine scandal. If Pence is also impeached and convicted along Trump, then US House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi would automatically become President. It’s a low probability event but not beyond the realm of possibility.

Finally, the regional Fed presidents who vote on the FOMC rotate every year. This year, two extremely hawkish people – Boston’s Eric Rosengren and Kansas City’s Esther George – will be replaced by two somewhat less hawkish people – Cleveland’s Loretta Mester and Philadelphia’s Patrick Harker. Pretty dovish Charles Evans from Chicago will be replaced by centrist Robert Kaplan of Dallas, while uber-dove James Bullard, of St. Louis, will be replaced by uber-uber dove Neel Kashkari.

Furthermore, Trump has nominated the very dovish Christopher Walker, the director of research at the St. Louis Fed, and the bizarre gold standard advocate, Judy Shelton, for the Fed’s Board of Governors. Walker is a conventional candidate and should have no problems being approved. Shelton is a bit more problematic. In any case, Walker should also help to tilt the discussion.

Net net, the composition of the FMOC will be slightly more dovish or less hawkish, whichever way you want to look at it. No one was forecasting a hike in rates anyway, but this change makes it more likely that US rates can only go down, not up, in 2020. That should be negative for the dollar at the margin.

The narrow range is also evident if we look at how the various currencies performed during the year vs the USD. The difference between the best-performing currency (CAD) and the worst-performing (SEK) was 10.4%, the second-narrowest range in the last decade. In fact, it’s the third-narrowest in the last 30 years (2004 was 5.8%).

The narrow range is also evident if we look at how the various currencies performed during the year vs the USD. The difference between the best-performing currency (CAD) and the worst-performing (SEK) was 10.4%, the second-narrowest range in the last decade. In fact, it’s the third-narrowest in the last 30 years (2004 was 5.8%).

The main reason for this narrow range, I believe, is the narrowing dispersion in economic performance among countries. If we look at the manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major currencies, the dispersion among them came down as the PMIs themselves came down. (Dispersion rose from June to September but fell after that.)

The main reason for this narrow range, I believe, is the narrowing dispersion in economic performance among countries. If we look at the manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major currencies, the dispersion among them came down as the PMIs themselves came down. (Dispersion rose from June to September but fell after that.)

Similarly, monetary policy also converged among the major countries. Policy rates came down for most major countries during the year. As they approached or pierced the zero bound, they tended to converge, since there is a limit to how low they can go.

Similarly, monetary policy also converged among the major countries. Policy rates came down for most major countries during the year. As they approached or pierced the zero bound, they tended to converge, since there is a limit to how low they can go.

Outlook for 2020: monetary convergence but economic divergence

This year, I expect we’ll see continued monetary policy convergence but increased economic divergence.

The market doesn’t see monetary policy pulling us out of these ranges in 2020. Most central banks are expected to be on hold during the coming year, with less than a 50-50 chance of a rate cut for most countries (and virtually no chance of a hike). Only Britain and Australia are seen as likely to cut. In the US, the market still expects a cut sometime in the second half, but the people making the decision – the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) themselves -- don’t.

In fairness, I should say that these rate forecasts are by no means guaranteed. For example, at the end of last year the market saw only a 13% chance of even one rate cut during 2019 in the US, but in the event there was not one but three cuts.

Outlook for 2020: monetary convergence but economic divergence

This year, I expect we’ll see continued monetary policy convergence but increased economic divergence.

The market doesn’t see monetary policy pulling us out of these ranges in 2020. Most central banks are expected to be on hold during the coming year, with less than a 50-50 chance of a rate cut for most countries (and virtually no chance of a hike). Only Britain and Australia are seen as likely to cut. In the US, the market still expects a cut sometime in the second half, but the people making the decision – the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) themselves -- don’t.

In fairness, I should say that these rate forecasts are by no means guaranteed. For example, at the end of last year the market saw only a 13% chance of even one rate cut during 2019 in the US, but in the event there was not one but three cuts.

However, economic performance may start to diverge as one of the major issues the currency market faced in 2019 will be less an issue in 2020: trade.

Trade has been the major uncertainty in the US since Trump started the trade war with China.

However, economic performance may start to diverge as one of the major issues the currency market faced in 2019 will be less an issue in 2020: trade.

Trade has been the major uncertainty in the US since Trump started the trade war with China.

All other major policy categories are currently at or below-average uncertainty, especially the two that the FX market usually focuses on: fiscal and monetary policy.

All other major policy categories are currently at or below-average uncertainty, especially the two that the FX market usually focuses on: fiscal and monetary policy.

It looks like trade will be much less of an issue in 2020 than it was in 2019. The US and China have signed “Phase One” of their trade agreement. While much of the details remain unclear, what is clear is that the US wants the issue resolved ahead of the November election so Trump can present some “wins” to those voters who still support him – not to mention get soybean prices up. At the same time, the US, Mexico and Canada finally signed the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The #1 problem that faced global financial markets in 2019 should be much less of a problem in 2020. That would be an enormous change. (Although of course we must remember those old sayings, “There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip” and “don’t count your exports until they’ve shipped.”)

The tit-for-tat tariffs had a huge impact on global trade and business sentiment. Many central banks also specifically mentioned trade uncertainties when explaining why they were cutting interest rates or keeping rates low.

It looks like trade will be much less of an issue in 2020 than it was in 2019. The US and China have signed “Phase One” of their trade agreement. While much of the details remain unclear, what is clear is that the US wants the issue resolved ahead of the November election so Trump can present some “wins” to those voters who still support him – not to mention get soybean prices up. At the same time, the US, Mexico and Canada finally signed the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The #1 problem that faced global financial markets in 2019 should be much less of a problem in 2020. That would be an enormous change. (Although of course we must remember those old sayings, “There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip” and “don’t count your exports until they’ve shipped.”)

The tit-for-tat tariffs had a huge impact on global trade and business sentiment. Many central banks also specifically mentioned trade uncertainties when explaining why they were cutting interest rates or keeping rates low.

What might be the implications of fewer trade worries?

Less “risk-on, risk-off” movement. Many trading sessions were dominated by whatever ambiguous tweet or headline in China’s Global Times appeared that day. Fewer such interjections may result in less volatility for the AUD/JPY. In theory it should also result in a higher AUD/JPY too, but of course that depends on there being no other risks to take its place – something I wouldn’t be so sure of. Just look at what happened with the US and Iran recently.

Less likelihood of rate cuts Many central banks have pointed to trade concerns as weighing on their economies. For example, ECB President Lagarde said last month that “The ongoing weakness of international trade in an environment of persistent global uncertainties continues to weigh on the euro area manufacturing sector and is dampening investment growth.” Similarly, the Bank of Canada said, “ongoing trade conflicts and related uncertainty are still weighing on global economic activity, and remain the biggest source of risk to the outlook.” If the global trade disputes die down, that could relieve some of the concerns of central banks. It doesn’t make rate hikes more likely, but it could make rate cuts less likely. That would mean less monetary policy convergence at the bottom and greater support for those currencies with relatively higher interest rates: USD, CAD, and NZD.

What might be the implications of fewer trade worries?

Less “risk-on, risk-off” movement. Many trading sessions were dominated by whatever ambiguous tweet or headline in China’s Global Times appeared that day. Fewer such interjections may result in less volatility for the AUD/JPY. In theory it should also result in a higher AUD/JPY too, but of course that depends on there being no other risks to take its place – something I wouldn’t be so sure of. Just look at what happened with the US and Iran recently.

Less likelihood of rate cuts Many central banks have pointed to trade concerns as weighing on their economies. For example, ECB President Lagarde said last month that “The ongoing weakness of international trade in an environment of persistent global uncertainties continues to weigh on the euro area manufacturing sector and is dampening investment growth.” Similarly, the Bank of Canada said, “ongoing trade conflicts and related uncertainty are still weighing on global economic activity, and remain the biggest source of risk to the outlook.” If the global trade disputes die down, that could relieve some of the concerns of central banks. It doesn’t make rate hikes more likely, but it could make rate cuts less likely. That would mean less monetary policy convergence at the bottom and greater support for those currencies with relatively higher interest rates: USD, CAD, and NZD.

Better performance for Europe

Germany is the dominant economy in Europe, with twice the impact on overall Eurozone GDP that would be expected simply from its weighting in EU statistics. And Germany has been the major victim of the global trading slowdown, not China. An improved trade picture suggests a better German economy and therefore perhaps a higher EUR/USD.

Better performance for Europe

Germany is the dominant economy in Europe, with twice the impact on overall Eurozone GDP that would be expected simply from its weighting in EU statistics. And Germany has been the major victim of the global trading slowdown, not China. An improved trade picture suggests a better German economy and therefore perhaps a higher EUR/USD.

Better performance for China, too

It’s only reasonable that the Chinese economy would benefit from the end of the trade war too. However, it’s hard to say if China’s current economic problems stem from international trade or from domestic debt woes. If indeed China’s economy did pick up, that would be positive for the commodity currencies, especially the AUD.

A weaker dollar

The dollar tends to benefit during extreme periods either way. When times are good, usually the US economy is among the best-performing economies, US interest rates move up, and the dollar does well. When times are bad, global investors look for a safe-haven, and the dollar is the safest haven of all.

But when times are so-so – not great but not bad either – the dollar tends to perform mediocrely. That could be the case this year too.

One possible exception: as shown above, dollar interest rates are the highest among the G10 countries. In a more stable environment, the USD could find demand as an asset currency for G10 carry trades. I think this is somewhat of a low possibility however, as carry trades are no longer as big a factor in the FX market as they used to be.

Better performance for China, too

It’s only reasonable that the Chinese economy would benefit from the end of the trade war too. However, it’s hard to say if China’s current economic problems stem from international trade or from domestic debt woes. If indeed China’s economy did pick up, that would be positive for the commodity currencies, especially the AUD.

A weaker dollar

The dollar tends to benefit during extreme periods either way. When times are good, usually the US economy is among the best-performing economies, US interest rates move up, and the dollar does well. When times are bad, global investors look for a safe-haven, and the dollar is the safest haven of all.

But when times are so-so – not great but not bad either – the dollar tends to perform mediocrely. That could be the case this year too.

One possible exception: as shown above, dollar interest rates are the highest among the G10 countries. In a more stable environment, the USD could find demand as an asset currency for G10 carry trades. I think this is somewhat of a low possibility however, as carry trades are no longer as big a factor in the FX market as they used to be.

Lower precious metals

Gold and silver have been beneficiaries of the increase in global risk during the year. With this risk gone, they may retrace some of their gains, assuming of course that nothing takes the place of trade as a new global risk – hardly a sure bet (again, Iran is “Exhibit A” here). There are always the “unknown unknowns” that we have to worry about. Also, a weaker dollar would temper the decline as gold tends to appreciate in dollar terms when the dollar weakens.

Lower precious metals

Gold and silver have been beneficiaries of the increase in global risk during the year. With this risk gone, they may retrace some of their gains, assuming of course that nothing takes the place of trade as a new global risk – hardly a sure bet (again, Iran is “Exhibit A” here). There are always the “unknown unknowns” that we have to worry about. Also, a weaker dollar would temper the decline as gold tends to appreciate in dollar terms when the dollar weakens.

Brexit: still a risk

With the Conservatives winning a decisive victory on the promise to “Get Brexit done,” will we finally be finished with this long-running drama on 31 January? Hah! True, the UK will probably leave the EU on schedule on 31 January. However, that won’t be the end of Brexit – it will just be the end of the beginning. In fact, the real battle will begin as soon as Britain leaves. Once Britain withdraws from the EU, the clock starts ticking for Britain and the EU to establish the nature of their new relationship. That’s actually a much harder task than the terms of the withdrawal. Furthermore, Britain will have to negotiate trade relationships with most other countries in the world at the same time.

And then there’s the question of “Scexit” and “Nixit” – Scotland and Northern Ireland leaving the UK. The former at least seems to be analogous to Catalonia as an issue even though the central governments oppose it.

GBP turned around from its lows and finished the year as the second-best-performing major currency in 2019 (best performing if you measure from the first trading day of 2019 to the last). Markets were reassured that a) Britain wouldn’t crash out of the EU without an agreement, and b) the appalling Jeremy Corbyn wouldn’t become PM. I’d be astonished though if that good performance were to be repeated in 2020. Given how long it’s taken Britain just to agree on a Withdrawal Agreement, I can’t see how they can work out a new trade agreement by the end of the year even if PM Johnson has written it into law. As a result, more uncertainty is in store for the GBP in 2020. Under those conditions, the Bank of England will have to keep rates unchanged at best – and the recent sluggish economic performance makes it likely that they’ll have to cut at least once during the year. I think GBP, the second-best performing currency of 2019, could be the worst of 2020.

Brexit: still a risk

With the Conservatives winning a decisive victory on the promise to “Get Brexit done,” will we finally be finished with this long-running drama on 31 January? Hah! True, the UK will probably leave the EU on schedule on 31 January. However, that won’t be the end of Brexit – it will just be the end of the beginning. In fact, the real battle will begin as soon as Britain leaves. Once Britain withdraws from the EU, the clock starts ticking for Britain and the EU to establish the nature of their new relationship. That’s actually a much harder task than the terms of the withdrawal. Furthermore, Britain will have to negotiate trade relationships with most other countries in the world at the same time.

And then there’s the question of “Scexit” and “Nixit” – Scotland and Northern Ireland leaving the UK. The former at least seems to be analogous to Catalonia as an issue even though the central governments oppose it.

GBP turned around from its lows and finished the year as the second-best-performing major currency in 2019 (best performing if you measure from the first trading day of 2019 to the last). Markets were reassured that a) Britain wouldn’t crash out of the EU without an agreement, and b) the appalling Jeremy Corbyn wouldn’t become PM. I’d be astonished though if that good performance were to be repeated in 2020. Given how long it’s taken Britain just to agree on a Withdrawal Agreement, I can’t see how they can work out a new trade agreement by the end of the year even if PM Johnson has written it into law. As a result, more uncertainty is in store for the GBP in 2020. Under those conditions, the Bank of England will have to keep rates unchanged at best – and the recent sluggish economic performance makes it likely that they’ll have to cut at least once during the year. I think GBP, the second-best performing currency of 2019, could be the worst of 2020.

US impeachment & election

There’s going to be an impeachment trial in the US Senate soon. Given the Republicans’ stated refusal to obey their sworn oath and act as an impartial jury, it’s likely that the impeachment won’t result in Trump’s conviction – although you never know, anything could happen: the Republicans could have a change of heart; he could resign rather than face the trial; he could have a heart attack; or he could even flee to Russia! (Russian TV has already referred to Trump as their ‘agent’ and asked if they should get an apartment ready for him.)

The impact on the dollar is therefore likely to be similar to the impact of the ridiculous Clinton impeachment trial, i.e. not much impact at all. In fact the dollar rose once the Senate trial began in that instance.

US impeachment & election

There’s going to be an impeachment trial in the US Senate soon. Given the Republicans’ stated refusal to obey their sworn oath and act as an impartial jury, it’s likely that the impeachment won’t result in Trump’s conviction – although you never know, anything could happen: the Republicans could have a change of heart; he could resign rather than face the trial; he could have a heart attack; or he could even flee to Russia! (Russian TV has already referred to Trump as their ‘agent’ and asked if they should get an apartment ready for him.)

The impact on the dollar is therefore likely to be similar to the impact of the ridiculous Clinton impeachment trial, i.e. not much impact at all. In fact the dollar rose once the Senate trial began in that instance.

The US election should also be no obstacle to the dollar. On average, the dollar has risen during election years since 1976:

The US election should also be no obstacle to the dollar. On average, the dollar has risen during election years since 1976:

If we look at the range, from the worst-performing election year to the best, we see that even in the year with the worst performance, the dollar was fairly stable after the election.

If we look at the range, from the worst-performing election year to the best, we see that even in the year with the worst performance, the dollar was fairly stable after the election.

There is some question about what will happen to the dollar if and when Trump loses and a Democrat wins, particularly if the Democrat candidate is someone who isn’t particularly popular with Wall Street, such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. The fact is that historically, the dollar has done better under Democrats than Republicans, but initially that might not be the case if the new President is thought to be a radical break to past policy.

There’s an even more interesting issue brewing with regards to the Presidency. News has been seeping out about Vice President Pence’s involvement in the Ukraine scandal. If Pence is also impeached and convicted along Trump, then US House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi would automatically become President. It’s a low probability event but not beyond the realm of possibility.

Finally, the regional Fed presidents who vote on the FOMC rotate every year. This year, two extremely hawkish people – Boston’s Eric Rosengren and Kansas City’s Esther George – will be replaced by two somewhat less hawkish people – Cleveland’s Loretta Mester and Philadelphia’s Patrick Harker. Pretty dovish Charles Evans from Chicago will be replaced by centrist Robert Kaplan of Dallas, while uber-dove James Bullard, of St. Louis, will be replaced by uber-uber dove Neel Kashkari.

Furthermore, Trump has nominated the very dovish Christopher Walker, the director of research at the St. Louis Fed, and the bizarre gold standard advocate, Judy Shelton, for the Fed’s Board of Governors. Walker is a conventional candidate and should have no problems being approved. Shelton is a bit more problematic. In any case, Walker should also help to tilt the discussion.

Net net, the composition of the FMOC will be slightly more dovish or less hawkish, whichever way you want to look at it. No one was forecasting a hike in rates anyway, but this change makes it more likely that US rates can only go down, not up, in 2020. That should be negative for the dollar at the margin.

There is some question about what will happen to the dollar if and when Trump loses and a Democrat wins, particularly if the Democrat candidate is someone who isn’t particularly popular with Wall Street, such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. The fact is that historically, the dollar has done better under Democrats than Republicans, but initially that might not be the case if the new President is thought to be a radical break to past policy.

There’s an even more interesting issue brewing with regards to the Presidency. News has been seeping out about Vice President Pence’s involvement in the Ukraine scandal. If Pence is also impeached and convicted along Trump, then US House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi would automatically become President. It’s a low probability event but not beyond the realm of possibility.

Finally, the regional Fed presidents who vote on the FOMC rotate every year. This year, two extremely hawkish people – Boston’s Eric Rosengren and Kansas City’s Esther George – will be replaced by two somewhat less hawkish people – Cleveland’s Loretta Mester and Philadelphia’s Patrick Harker. Pretty dovish Charles Evans from Chicago will be replaced by centrist Robert Kaplan of Dallas, while uber-dove James Bullard, of St. Louis, will be replaced by uber-uber dove Neel Kashkari.

Furthermore, Trump has nominated the very dovish Christopher Walker, the director of research at the St. Louis Fed, and the bizarre gold standard advocate, Judy Shelton, for the Fed’s Board of Governors. Walker is a conventional candidate and should have no problems being approved. Shelton is a bit more problematic. In any case, Walker should also help to tilt the discussion.

Net net, the composition of the FMOC will be slightly more dovish or less hawkish, whichever way you want to look at it. No one was forecasting a hike in rates anyway, but this change makes it more likely that US rates can only go down, not up, in 2020. That should be negative for the dollar at the margin.

The year that just ended has been one of political turmoil, global uncertainty caused by Trump’s trade war, economic slowdown, and yet record-high stock prices coupled with near hibernation in the FX market. The year just starting is shaping up to be even more dramatic politically, with Brexit from January and the US impeachment trial and Presidential election later in the year. How will this affect currencies? Which currencies might benefit, and which might suffer?

First let’s look at why all this Sturm und Drang failed to make much of an impression in 2019.

There’s no doubt that the FX markets were in the doldrums in 2019. If we look at the range between the high and the low of each currency pair over a six-month window, we can see that the average hit the lowest level in two decades in July and ended the year not far off.

The narrow range is also evident if we look at how the various currencies performed during the year vs the USD. The difference between the best-performing currency (CAD) and the worst-performing (SEK) was 10.4%, the second-narrowest range in the last decade. In fact, it’s the third-narrowest in the last 30 years (2004 was 5.8%).

The main reason for this narrow range, I believe, is the narrowing dispersion in economic performance among countries. If we look at the manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major currencies, the dispersion among them came down as the PMI

To continue reading the full report, please Login to your QCS Holding Dashboard

Not an existing member? Register an account in a few seconds, and gain unlimited access to exclusive research resources.

Access Leading Analysis, Market Briefs & Reports, Daily Live Webinars and much more!

Disclaimer: The content on this website should not in any way be construed, either explicitly or implicitly, directly or indirectly, as investment advice, recommendation or suggestion of an investment strategy with respect to a financial instrument, in any manner whatsoever. Any indication of past performance or simulated past performance included on any page on this blog is not a reliable indicator of future results. For the Full Disclaimer please click here.